WALES: A PUBLISHING LACUNA

by ISHMAEL ANNOBIL

Here I am again, in Wales. Cardiff Bay shimmers in the evening sun, fully feathered like the eternal peacock it aims to become. What started as a place for contemplation has become a Rubik’s Cube. You must concentrate, if you are to pick your way through the cluster of eateries successfully and arrive at the only redoubt left, the quaint Norwegian Church. From the distance, the hallowed white structure seems to be standing prone on the water’s edge, as if it wishes to slither away to sea.

I enter it hastily to bury my head. Roald Dahl is said to have worshipped in it as a child (when it stood on it’s original plot in Llandaff). From her now gastronomical bosom I later hear or read about a boat trip to Penarth Pier, a stone’s throw away. I opt for the eye of the beautiful Celtic Ring (a bronze sculpture – or is it the oracle) instead, to capture incidental shots of the sea traffic for my documentary on an Egyptian poet based in Wales.

I wonder if my subject, too, senses the hyperactivity around us, or whether he, given his slight change in attitude, thinks Cardiff Bay is the bee’s knees infrastructure to put his native Cairo to shame. Naturally, we are both conscious of what this melee came to replace: an old seafarer’s community (properly called Tiger Bay). He once arrived at my door with an urgent wish to get published, and I founded an express publishing house to abide his dream. Where else could he go, given his cantankerous nature and his habit of wearing a giant crucifix over his shirt.

The whole idea of shooting Cardiff Bay for cinematic flourish rankles. For its part, it poses yet another antithesis to the craft of publishing. The sea seems to echo my thoughts. Its waves barely crack against the quay as they would have in its heyday; nowadays it shimmers just to please tourists, churned by a tyranny of outboard motors and frenzied seagulls, who have finally seen the sense in abandoning their Caroline Street fish and chips haunts.

This Cardiff Bay is not my mirror onto Wales; it doesn't reference the poetic fibre I spent eleven years savouring and helping develop. It has no room in its many chambers for publishing, and that troubles me greatly, for I have always believed that culture precedes industry. This Cardiff Bay is one of those showpieces meant to halo the Thatcherite dream of enterprise. It's was a rather slow birth, spawning many an apocalyptic tale during its gestation.

Of course, the real apocalypse was the erosion of the unique human culture of Tiger Bay, the truest form of natural cosmopolitanism ever spawned in the British Isles, to which Captain Scott had come to raise money and moral support for his expeditionary gig for Queen and Country (or was it King?). For symbolic refrain, I should point out that many of the old dockside buildings were moved bodily from their original foundations to vantage positions befitting the fanfare.

If you were an American 'nostalgiac' high on the vigorous timbre of Dylan Thomas' poetry, and perhaps are one of the few that could differentiate between the generic British Dylan and the authentic Swansea one, then you may sadly be a victim of imagined substance. But, of course, such imagining is understandable; it’s born of the logic that a literary nation begets literary publishing. The bad news is that Wales has no publishing industry!

Wales is a mere publishing appendage, whose sons and daughters ache to be heard outside the shores of this proud nation. Yes, her children still bristle with stupendous poetic atavism, and are probably the most lyrical people on earth. And despite the heady nationalism precipitated in part by industrial decline and the arrogant English bushels for self-determination and native lore, the collective Welsh artistic idiom is of the sort that delineates and overlaps sub- and surcultural stances with exquisite ease.

This is because the Welsh do really have it in bushels, and so have no need to hold any one away from it. It is part of the everyday; it rolls out on the tongues of the miner as well as the chaplain or professor. But publishing industry it has not. If Wales has any constant at all, it’s its ability to convince you at all times that it’s a burgeoning nation. Its achievements smack of attempts; its triumphs smack of defiance (defiance being a sort of diffidence), what with the goose-pimply euphoria that greets local champions. Meantime, nostalgia is the opium. It has become an industry. It sustains the phoney, salaried custodians who think learning to speak Welsh is all there is to it.

So the truly inspired people that can actually tap into the aforementioned atavism are woefully stymied. A good example is the acid campaign being presently waged against Bragod, a pristine antiquarian musical duo whose thankless job is the revival of obscure, medieval music and instruments, including the Crwth (a ancient harp).

But I must stay on course. I must turn the nation over and see what publishing fibre actually falls out of its pockets. Tôpher Mills, a great, young poet, is the father of the small press in Wales (I don’t care what anyone says to the contrary). With his Red Sharks Press, he managed to publish most of Wales’s modern poets, selling his books from pub to pub and through the one remit-bound Arts Council of Wales bookshop, Oriel, in Cardiff.

Naturally, the Arts Council failed to see him as the phenomenon he really was, especially because he also turned out to be quite an eloquent polemicist against them. Sometime in the 90s they tried to woo him with a stipend, which they quickly withdrew for his supposed failure to keep up with another of the Council's anachronistic ideas.

That is not to say nothing is happening now, but whatever it is that flies the flag today has no voice outside Wales. I know this, I moved to London six years ago and I still can’t hear a whimper. Since Tôpher’s Red Sharks Press, a few magnificent things have happened, including my own Circa21, Wales’s first serious English language arts newspaper, which, as can be imagined, foundered magnificently by the roadside in 1996. The Arts Council of Wales knows why. Alas, nothing has come to replace Circa21 yet, or even attempted to.

Most Welsh book publishing is still done mainly by the small press. Of course, we encounter the superb efforts of Gomer Press and Seren, as always, but even they would admit that the actual frisson of publishing and vying for shelf space internationally is well out of their reach. They would also admit that they are hemmed in by the backward funding and logistical packages they receive from their Arts Council.

Admittedly, I would rather have a private publishing industry that calls its own shots, sets its own agenda and trends, and competes editorially and commercially. Public funding amounts ultimately to corralling. For that matter, the challenge is to businessmen and development agencies to wake to the potentials of the publishing.

If the small press should soar above the parapet, then it must have actual development grants and loans through an integrated bank/government scheme, which fosters independent corporate structures, and not the overweening franchises the Arts Council and its agencies administer.

After all, franchise is subject to numerical strictures. It muffles tone and cosmopolitanism. It insists on a localised agenda. It ensures that the quieter voices within literature are never heard, and it keeps Wales cosily ensconced at the starting blocks, forever underrated by all and sundry.

Of course, there is some scholarly publishing, mainly by the University of Wales Press. But I dare not include that in this estimation, as it belongs with other echelon – namely, the global trans-campus sector. Contemporary writing has never really had a platform in Wales. Even Dylan Thomas had no platform in Wales, leading some deluded English commentators to say, “The Welsh are an unqualified audience for Dylan Thomas”.

That Dylan had to pack his bag and venture beyond the idyll of his Welsh boathouse to find solace elsewhere tells of the dire nature of the publishing lacuna that is Wales. His plight and subsequent over-compensating with alcohol is a heavy paradigm, and my beloved Wales cannot shake it off its back in a hurry.

But to have a publishing industry is to have a distribution industry, and Wales has but a dearth of it. The Welsh Books Council has a remit to distribute books, but mine and others I know of have never received any shelf space. Commercial distribution of Welsh published books is almost non-existent.

So I leave these shores again with nothing but a cassette of videofilm, which will invariably fire an aside or two against the common anathema to Welshness – The Arts Council of Wales. I also have a headache. Maybe it is unrequited love. Whatever it is, I know my being described by my contemporaries as a half adopted Welshman has nothing to do with this survey (I am but Wales' Ghanaian lover), but it determines my disdain for the myopia and hanky-panky of those with the power to change things but can't or won't. I am particularly disdainful of their forcible, delusional and hypocritical nationalism.

I wish them hawddamor, for the true Welsh are coming!

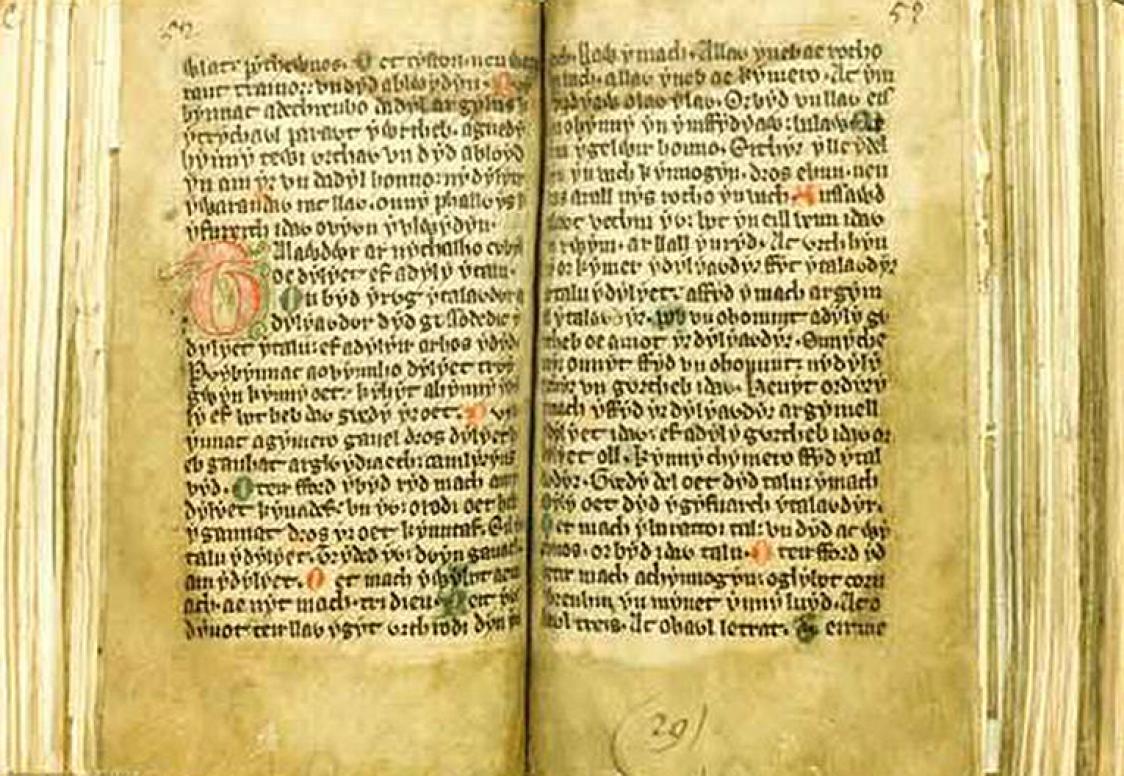

Photos:

1. The Laws of Hywel Dda, attributed to Howel the Good, king of Wales (c.880-950)

2. Cardiff Bay, coutesy of Wikipedia