Poetry & Prose : CRISPUS ATTUCKS (Chapter II)

(Chapter II)

CRISPUS ATTUCKS

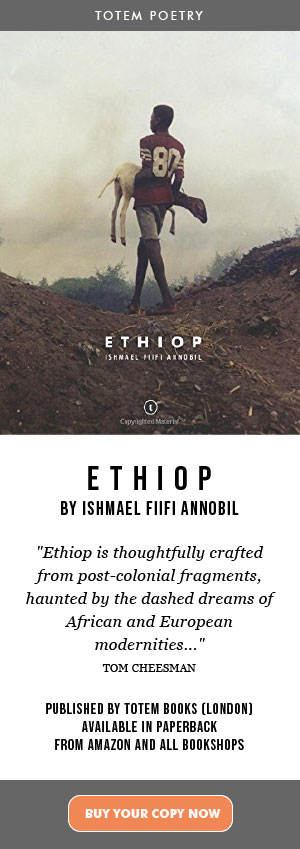

By Ishmael Annobil

So Crispus Attucks took quickly to reassessing of the facts. The first man to die for American was the one living there before the ‘invasion’: Native American. That forefather had died to maintain that original state of affairs, for the right to love – even the invader – and be respected for it; but even he had failed to push back the tide of European hunger – hunger for land, for money, for the soul, for, for... Today, that forefather was a caricature of himself, at once vilified and deified by Hollywood - to justify and remit the guilt.

The original Crispus Attucks had died alongside one group of Europeans fighting against other Europeans, in a European war designed to turn the invader into a patriot. In retrospect, he had wasted his life. Today he couldn’t be found easily in any history book. Caucasian America had sunk him. The same way it kept polishing up the tale of Wounded Knee, in its maniacal attempt to bury its shameful massacre of a people doing a death dance. The same way it was systematically pitching Castor’s disgraceful defeat as the epitome of valour. The whole thing (the propaganda, that is) was a purge.

But Crispus was too intense a dreamer to give up on America just because of the doings of the other half, for that was the intended outcome of all the lynchings and mockery that had gone on. He was no fool to fall for that kind of trick. After all, he’d come under the 'guise' of a liberation fighter. And though he hadn’t lived up to it, he could at least press for a spiritual victory. That way, he could also live with his regret for coming to America, for America had indeed been a torture to his soul.

He rolled off his bed, sprightly old goat, and sat centre-stage in his sparse apartment. His jazz records, his only true material possessions (everything else had been rescued from the dump), stared at him through the burning sun beam that had him lit up like some idol, like Jimmy Smith or something. The records inhabited the brown formica clad wall unit like epiphytes. He'd rescued that piece of retrogressive furniture from the back of the Korean neighbourhood multi-store. He stared back at the records, reading their spines in turn. He did so every morning and night. He was particularly hooked on Jimmy Smith.

Just before he started to curse himself for rising so late, he remembered he was on retirement. He smiled at the prospect of uninterrupted days and days of Jazz, in this sullen Summer heat: Jimmy’s erudite, calming organ, the cleaving guitar riffs, the cocky edge of drum and cymbal, probably Ziljian. While he dreamed, a roach emerged from behind the gaping skirting board and ascended the wall arrogantly into his peripheral vision, and then raced along to rest on the spines of the records. It cleaned its antennae, then started to jerk back and forth, as if to command his attention. It threatened his bliss. His fury. He grabbed an old shirt and tip-toed like a devil toward the insect, but before he could do his boomerang manoeuvre to swat the damn thing, it flew over his head and landed on his bed. Spurned, he chuckled: “Now you wanna get into bed with me, sucker? Git off ma bed! Gi orrf ma bed!”

Then his African superstition caught up with him - what if the roach was a transmuted witch out to get him, what with all that retirement money dropping into his bank account by now? But then his mind pivoted weirdly, and he reckoned he could do with any old seductress sent this side of life to help blow the money. Money was exorcism. Life was too short. Been too lonely for too long. So his superstitious heart dared the roach to change back immediately into a human woman. He was in the realms of magic realism. He sat back down on the chair. He imagined tiny ebony thighs shooting through the flimsy body of the insect and bloating forcefully into luscious things, topped with a bushy triangle...

Meanwhile, nature willed him to reach for the remote control to resume viewing the porno video from last night. The treachery of solitude. The telly started with a loud moan and, suddenly, a self-loving Aphrodite lay before him, startling him with her illicit rawness, her edge. The blade of society’s underbelly. The sin. His mind screamed at her loud gurgling groan. “Trash,” he thought. Titillating, but too loud. Her adult noise would betray him to his neighbours. He fumbled frantically with the remote to gag the video machine. He hit the wrong button and raised her voice instead. He flew off his chair with a thumping heart and pulled out the plug altogether. He wasn’t one for technology. The scorned video phewed like a gased athlete and withdrew its light. Fact was, he needed female company now, more than ever before. A void had been roaming in him, since the farewell party.

He might hit the park and hitch up with some giddy, tattooed bird, to preserve his life with. He needed thunder. Perhaps, he could help arrest Caramanca’s aching too, by supplying him with one. He was loaded, and he couldn’t be stingy towards a fellow old man. Money was like camphor to him nowadays, ever since he got the notion of retirement pay into his head. It swept away the dankness of his age and lifestyle. It burned his groin with anticipation. But, he was also troubled by a nebulous material anticipation. It had to do with what to do with the money. There was the remote possibility of switching zones and buying himself a wood cabin up country, maybe Canada, but he hadn’t quite got over his groin’s burning for woman, to be able to settle into real estate matters. He needed to marry first. He needed an heir, badly.

He got up from the chair and shambled to the sink to wash (he never used the communal shower and bathtub. The rats had cornered them for a boudoir). He planned to don his streetwise jeans and black leather jacket for the hustle. He ignored the roach; even thought of letting it scare the living daylight out of the prostitute that came home with him. Only then, Caramanca destroyed the idyll - he wailed suddenly like a distraught moose. The wail travelled through the walls, and rankled like a cobra’s hiss with Crispus’ hangover. A Puerto Rican voice bellowed in response:

“Shut the fuck up - sucker!”

The usual routine. First Caramanca would wail, the Puerto Rican, Julio, would blast at him; Caramanca would do it again, and the blasting would rise to a fever pitch, till Julio started to cough painfully, then Caramanca would shut up as if in sympathy to his adversary. Crispus couldn’t be sure, but he suspected the old fighter did it on purpose to get attention; any kind of attention.

Before stripping down for his wash, Crispus lay a Jimmy Smith on the turntable and fired up his room with Organ Grinder’s Swing. He played it very loud, as if to fumigate the place with it. Then he placed a wide enamelware bowl at his feet. He would stand in it and scoop the cold water from the basin over his him. Almost as good as a deep wash. He never understood how others managed with just a damp flannel - massage, he called it. He heard a faint tap on his door, followed by a fawning enthusiasm: “More, Crispo, more of that!” It was Julio, who had recently developed a love for jazz. Crispus didn’t need to get the door. Instead, he nodded a kind of kool half-smile nod, old as he was, at his own goatied reflection in the mirror and mumbled back something through his toothpaste filled mouth. He took his shallow ablutions in great cheer and stepped out of the bowl like a baptised sinner.

For a moment, the music took him off the shelf, moving his feet into festive gear; sliding and tapping. Hooha! If only he had a woman lying right there in that bed watching him do his thing - an eligible man about to enter money, fifty-something years worth of it. There would be thunder, he thought. He was given to simple fantasies, simple pleasures, quite missionary in the extreme, all bordering on the simple urge for procreation, though he dared not acknowledge it. But modest though this urge was, it had all the relative dynamism of the mating season of big cats. Pushing seventy, he was in a hurry to spread his seed.

Yet, if America had anything he really prized above all, it was her ability to keep her inhabitants from growing up. Or letting up. But he knew that, in his case, it was the not having a certification of his belonging that kept him holding on to his youth, mentally speaking. He was still an illegal citizen after fifty-six years in the U.S. Never tried to get straight with the powers that be, for fear of being thrown out. And so he never thought of revisiting his own country. How would he get back into the US? Faking identity involves many more crimes, each to cover up the last one. He would need to answer for the entire chain of associated crimes at immigration.

Of course, when he'd chosen to call himself Crispus Attucks, he’d hoped to push a sentimental button with history-minded African America. But soon after the deed, he’d found that he had no real reason to hope or worry: the great historical exploits of African Americans were, to the average African American hood, as safe as ignorance. A shout in a well, whose echo bore the question: “Crispus who?” Fact is he’d read of the exploits of his namesake in an obscure Harlem newsletter he found lying in his hideout on the ship he ‘commandeered’ to the US. It had kept him company throughout the journey.

The hideout had been the space under an African American sailor’s bunk. The guy had taken to him and his burning wish to hustle the US for payback, like he would a liberation fighter - Crispus had flashed a borrowed WW1 campaign medal at him, you see, at a beer bar in Accra. The sailor had smuggled him aboard, wrapped up as an ebony carving. (He'd strapped Crispus up into a mummy and instructed him to be as stiff as death then fitted him into a sisal sack.) After seven long weeks, the steamer had finally reached home. His sponsor had smuggled him off the steamer, disguised this time as a sack of cocoa beans, armed with a penknife for his self-delivery. Care was taken to drop the living sack onto the pallet last, beyond the reach of any customs officer’s assaying knife. From his sarcophagus Crispus had prayed for sun. The winter nearly shrivelled his heart. After six hours, the pallet had ended up in a bonded warehouse in Brooklyn. He had emerged from the sack at around midnight. The rest was history.

He’d gone on to acquire a Social Security number through such a web of deceit and luck that, even he would be too irked to try remembering it all. But he could still remembered with joy how he’d faked being a dumb and deaf illiterate, to carry it through. He could also remembered the bogus, long leather coat and fedora wearing psychiatrist the sailor had assigned him, to help him pull it off. He never saw the sailor again. Rumour was, the kind man had been made to walk the plank (in a sack, that is) for aiding stowaways from Casablanca. But Crispus refused to believe that; especially because another sailor, a Greek American, had told him that Joe ‘Africanus’ Minks (Crispus’ smuggler) had married a Moroccan Berber woman, and settled, indeed, in Casablanca, where he ran the only sailors’ tavern.

Either way, Crispus figured that the smuggling had had something to do with his friend’s continued absence from the US. “To think the man just did it to help desperate people! Surely, someone has to proclaim his sainthood,” Crispus always thought. And that heavy guilt-laden sentiment always stopped him from believing the man was dead. Guilt-laden because he reckoned, if he hadn’t enticed the sailor’s charity in the first place, then he wouldn’t have got so obsessed with sharing America and got into trouble.

But all that mattered today, the day after his retirement, was his Americaness. His self-decreed honorary status. A very organic feeling thing which smelt like atavism, and only allowed his true self to writhe only at night, when darkness and loneliness brought the notion of self into full view. This, however, had caused a division in him, which manifested in his obscure but warm manner. The inner-city dichotomy. It made him feel obliged to work Americanism to death. To be alert to it. So he wilfully sought after any opportunity to talk too much, to show off his ‘native’ lilting twanging slang thing; he collected Americana like a tourist; he debated America’s hallowed sports, baseball and basketball. He wore the team stripes, and invented historical sporting moments to shock fellow connoisseurs with (the Attucian Apocrypha).

And he had the God-given memory to uphold it all, never tripping himself in a heated debate. For he had to believe in his own lies enough to tell them - they made sense to his surreal, highly-strung fugitive’s mind; the same way a neglected child invents rich uncles. He’d become, by sleight of mind, a trough of American sporting knowledge, and no one, not even the earth could play him at it. That was his specialism; in America everyone had a specialism, often intended for their prophesied fifteen-minute fame. The totally untalented might commit murders for attention.

Benign though Crispus’ psycho-generative output might seem, it did have victims; same way readers of Alain Quartermain’s King Solomon’s Mines stay permanently misinformed about Africa. Partially because of this, and his irregular status in the US, he lived in fear (the Christian man); he lived in permanent anticipation of a bust. So he had kept his personal effects minimal. He preferred money to domestic comforts, because money could be transacted to and from anywhere, busted or not. His bank account at the Brooklyn branch of the Chemical Bank held a handsome wad (he refused to acknowledge the figure himself, in case the word slipped out amongst thieves).

But it was high enough to warrant a home visit from the bank manager. So his feet had never gone anywhere near that bank. He deposited and withdrew his money at other branches instead, to shake off any bank-managerial sycophancy. He couldn’t give a hoot about the life assurance policies or bonds they tried to flog old wealthy customers. All that mattered to him were the green sheets of paper that said, ‘In God We Trust’.

Illustrated by Ishmael Annobil